Decisions, Decisions

According to Webster’s dictionary, a decision is a determination arrived at after consideration. Yet why, even after careful thought and consideration, do we still make bad decisions?

To better understand decision-making, we’re first going to look to Danny Kahneman, a behavioral psychologist who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2002. Kahneman focused his career on judgment and decision-making and the key elements that explain how and why we make the decisions we do.

These key elements, known as heuristics in psychological terms, are the rules people often use to form judgments and make decisions. They are mental shortcuts that usually involve focusing on one aspect of a complex problem and ignoring others.

Kahneman found that heuristics were highly economical and often effective, but they continuously led to systematic and predictable errors. He reasoned that if people could better understand the heuristics and the biases to which they are tied, they could improve judgments and decisions in situations of uncertainty.

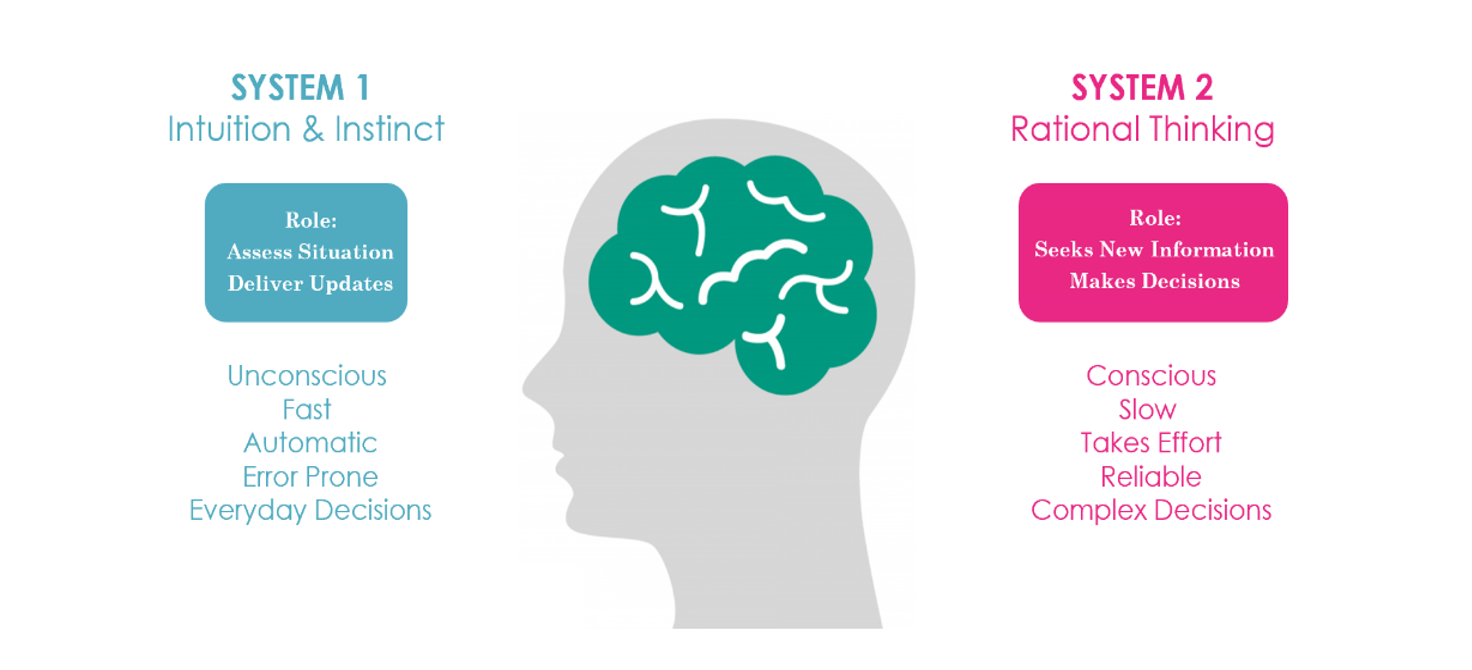

Prior to Kahneman, the world of economics operated by the assumption that humans are rational beings. As such, economic models were built and used assuming that we are all able to consciously tap into rationality. What Kahneman found, however, is that there is something else driving decision-making. Kahneman named this other decision-making driver System 1—intuition and instinct—in a two-part system in which System 2 is rational thinking.

Kahneman and a colleague, Amos Tversky, set out to test these decision-making systems in 1983. A famous example from their research is The Linda Problem, also known as the conjunction fallacy.

The Linda Problem

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and she also participated in antinuclear demonstrations.

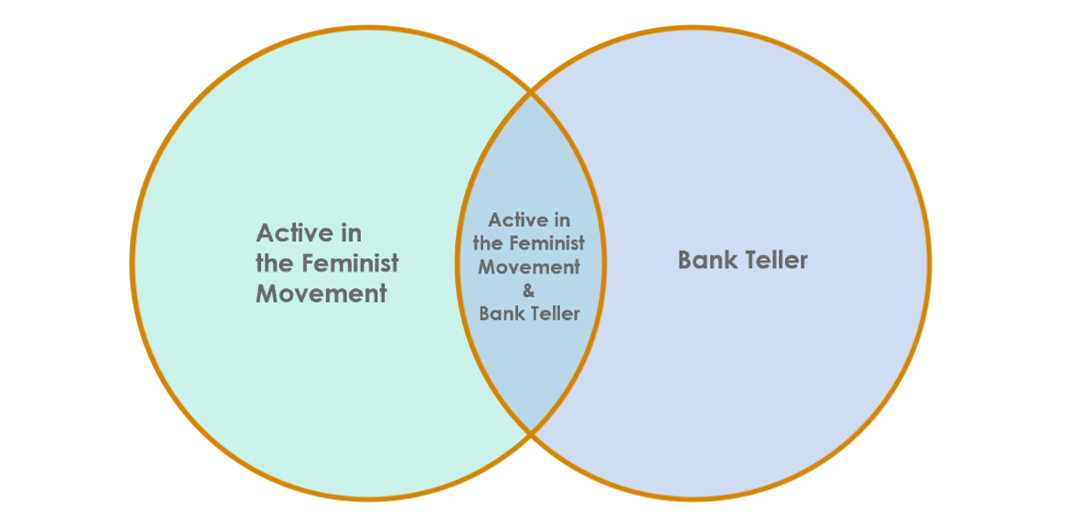

Which alternative is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

If you answered “1” you are correct! Because there is a tendency to think that more information makes something more probable, people fall toward “2.”

Judgment can be distorted because the character sketch is representative of a person who might be an active feminist but not of someone who works in a bank.

Many of us instinctively make poor initial decisions and then spend valuable time and resources correcting them. So the question is, how do we tap into System 2—rational thinking—instead of defaulting to System 1—intuition and instinct?

We know that System 1 is triggered by our default instincts, so the goal is to activate our less instinctive System 2 more readily. The roadmap to System 2 requires the use of mental models, or ways in which we understand and simplify the complexities of the world.

Shane Parrish’s Farnham Street blog is designed to help people master what others have already figured out, and in this case, we’re looking at mental models for better decision-making. With over 100 different types of mental models, the top 3 thinking frameworks according to Farnham Street are the following:

- Inversion: a problem-solving technique; thinking through something in reverse

- Second-Order Thinking: deep, complex thinking that deliberately considers consequences, thinking in terms of interactions and time

- The Map Is Not the Territory: the map of reality is not reality itself; it is a condensed snapshot taken at a specific moment in time

Throughout our lives, we spontaneously use many mental models, but the key is to actively remember that they are there. When you get stuck, leverage an active awareness of your remembered models to come to your aid. Even better, try to incorporate the mental models of others into your own library. Farnham Street gives a great example of the practical importance of using multiple mental models. Looking at a forest, a botanist may think of the ecosystem, an environmentalist may dwell on climate change, an engineer looks at tree growth, a businessperson the value of the land. None are wrong, but to grab the low hanging fruit here, they may all individually struggle to see the forest through the trees. So the next time you have a decision to make, pause, open your mental model toolbox, and fight the urge to let your intuition and instinct take over.

References

- A framework for making smarter decisions and fewer errors. Farnham Street. https://fs.blog/smart-decisions. Updated 2020. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- Mental models: the best way to make intelligent decisions (109 Models Explained). Farnham Street. https://fs.blog/mental-models. Updated 2020. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Extensional versus intuitive reasoning: the conjunction fallacy in probability judgment. Psychol Rev. 1983; 90(4): 293–315.